I am honored to welcome a special guest to the blog today. Phil Clarke, a debut author, joins me to discuss his thought-provoking novel, Falling Night. This poignant narrative delves into the harrowing experiences of both aid-workers and locals amidst the turmoil of an African civil war.

In Falling Night, the protagonist, an aid-worker, grapples with the moral dilemma of balancing his desire to help those in need with the constant threat to his own safety. Through his journey, he discovers a remarkable resilience and finds solace in the midst of chaos.

Join me as we delve into the inspiration behind Falling Night and much more.

Hello Phil and welcome to my blog, The Book Decoder. Please tell me and my readers about yourself.

Hello Rekha and readers! I was born and educated in the UK, and then spent 7 years as a tropical forest biologist and aid worker in Africa and the Middle East during the 1990s. After that, I was director of the Danish branch of the international medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders for nearly nine years.

I left to start an independent war crimes investigation agency called Bloodhound; one of its various aims was to bring a Swedish oil company to justice for complicity in war crimes in Sudan during the civil war.

I was unable to raise money for this venture, but just as my finances were about to go under, I was offered a job as a cook on a mineral prospecting expedition in Greenland. For the next seven years, I did various logistics and admin jobs for the company, and during my last field season in 2014, I restarted writing ‘Falling Night’ in my spare time while I was camp manager for a drilling project.

The novel had lain dormant for 10 years, and it felt right to restart it. Writing the novel and then finding a publisher took up much of my time over the following years – it proved to be a much harder task than I had expected.

Tell us about your debut novel, Falling Night.

‘Falling Night’ is one of the very few aid worker novels ever written. Many aid workers write memoirs about their experiences, but these can be confusing reads, because aid workers often work for short periods in many different conflict contexts.

This means that much space in these books has to be dedicated to explaining the political background to where the aid workers have been. I therefore saw fiction as a way around this, enabling me to gradually develop a political context throughout the storyline of a novel, so that readers can live through the events as they progress.

A novel also provides the additional advantage of restricting the number of key characters and permitting their personalities to be slowly revealed as the narrative unfolds. It also avoids any risk of insulting real people, and thus allows an author to be more frank about the characters’ foibles.

Can you share some insights into your personal experiences as an aid-worker in Africa and how they influenced you to write Falling Night?

Before becoming an aid worker, I had spent three years living in basic conditions in remote, under-developed areas of Tanzania. I was with a small team of biologists leading groups of students from the UK to conduct biodiversity surveys in the surviving patches of tropical dry forest near the coast. We would clear a patch of bush for our camp, put up tents, dig a well for water, and another pit at some distance for our toilet.

Our neighbours were subsistence farmers who lived in thatched wattle and daub houses with few possessions. I thus became accustomed to seeing extreme poverty but was profoundly shocked when I became an aid worker by how much worse life is for people who are victims of war. Telling that story, in way that is accessible for readers, was a key goal behind writing ‘Falling Night’.

Did you face any challenges while writing about traumatic events such as human rights abuse, genocide, and cannibalism? How did you navigate them?

The biggest challenge was to get the right balance in the novel between generating feelings of horror, pity, shock etc. without being too graphic that would risk traumatising the reader. I had to edit my texts hundreds of times in my attempt to achieve this, and during each pass I would change a few words to improve the narrative, again and again until I felt I had got it right.

I then asked 12 friends to read through the novel, and amended the text according to their feedback. They were a huge help and support for the ‘Falling Night’ project, and I will always be grateful for the considerable time they spent reading through my earlier and less polished drafts of the manuscript.

Another challenge was how to portray the reality of Africa’s wars without singling out that continent for criticism, which is why the novel includes reflections about similar wrongs being committed in or by Western countries. We are all alike as humans, and apparent differences are mainly because some of us are fortunate that we were not born in countries ravaged by war and/or corruption.

The protagonist’s journey in the novel involves personal growth and spiritual discovery. Was this aspect influenced by your own experiences or observations?

Yes, very much so. I had some profound spiritual experiences during my years as an aid worker, when it was very evident to me that my life was supernaturally spared on many occasions. I also became aware that God had planned some tasks that He wanted me to carry out, while leaving me with the choice of whether or not to do them. One of these tasks was to write a novel to reveal what really happens in some of Africa’s wars.

What do you hope readers will take away from Falling Night after reading it?

Firstly, I want them to feel that the book was worth reading. I am well aware as an author that I have created a product that requires a chunk of people’s valuable time if they are going to read it, so I don’t want them to feel that time was wasted.

Secondly, I want readers to feel they have acquired a fresh understanding of what happens in some of Africa’s wars, for example about the suffering of the victims and of the role and motives of the United Nations and relief agencies to bring assistance.

Can you share any anecdotes or memorable moments from your time as an aid worker that directly influenced scenes or characters in the book?

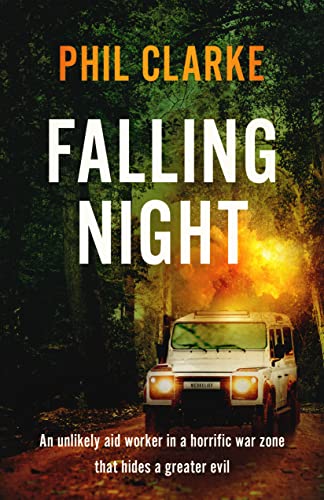

The cover image of ‘Falling Night’ depicts a Land Rover driving through a forest at night, which portrays a scene in the novel. It was inspired by a powerful experience that I had on a river journey in Sudan during the civil war in the year 2000, when I sensed something very bad was about to happen to me.

Thus, the vehicle in ‘Falling Night’ was a boat in my reality, while the actual setting was a river journey in swampland rather than a fictional road trip through a rainforest, though my descriptions of that road trip at night are inspired by many night journeys in the forests and savannah of Tanzania when I worked there as a biologist. The consequent events described in the novel, and the main character Alan’s thoughts, are similar to those I had on that fateful river journey in Sudan. I don’t think it would be possible to imagine such experiences – they have to be lived.

The characters in the book are fictional, but the expat team broadly encompass the motives and personalities of people who become aid workers. Other characters come and go in each chapter, reflecting the incredible diversity of people you encounter as an aid worker – in my case, the celeb list includes a UN Secretary General, the Pope, an ex-President, a Nobel Prize winner, a few royals, a famous rock star, plus some seriously unpleasant war criminals.

Most were mainly memorable for being famous, but I also got to meet many amazing people who impressed me by their passionate dedication to assist those in need. A smattering of such people are therefore included in the novel.

What’s next for Phil Clarke? Are you currently working on any projects?

I am the kind of person who always has many projects on the go at any time, which has the disadvantage that they tend to take ages to complete. ‘Falling Night’ took 25 years from start to print, and required some 7,000 hours to complete. A sequel is on its way, but will take some time to finish.

Another project that I am currently involved in is a small Danish NGO which has the objective to promote carrot cultivation in Ethiopia as a means to combat vitamin-A deficiency. We are about to harvest 150 Kg of carrot seed that amounts to some 75-150 million seeds that will be distributed for free to Ethiopian farmers. We have also produced detailed photo manuals in the main Ethiopian languages to explain how best to grow carrots and produce seeds from them, so that farmers will be self-sufficient in carrot cultivation for a number of seasons.

It is a real pleasure to be involved in a project that is so positive and does not have any nasty aspects, given that I have spent so much of my life working in and then writing about war.

Leave a comment